Lesbian/Bi Stories Can Absolutely Be Universal

By Trish Bendix on June 10, 2015

What makes something queer? Is it the person behind the television show or movie, or a character that sleeps with the same sex? Maybe it’s the subtext alone that some consumers latch onto while others remain oblivious. Queer stories (which is to say things that are not 100 percent heterosexual) have become a sizable part of the zeitgeist over the last three decades, and mainstream culture is better off for it. Queer culture has, of course, existed—and persisted—but largely on the fringe, and many of our stories have been reshaped for mass consumption, straightened out and de-gayed so that characters might be more “relatable.” (See: Fried Green Tomatoes.)

And yet while LGBT books, TV shows, movies and Broadway shows have been given awards, spawned critical acclaim, and growing fanbases, there’s still a pervasive idea that suggests the people behind them (writers, producers, networks, actors, etc.) must prove that their work is not “just a gay story.” Fun Home‘s playwright Lisa Kron addressed this in a recent interview, discussing how people qualify the butch lesbian-led show by saying it’s “much bigger than the story of a lesbian.”

“I say, ‘It’s EXACTLY the size of the story of a lesbian,” Lisa told The New York Post. “The presumption is that this type of person can’t reflect something fundamental about the human experience. I’m neither Danish nor royal, but I don’t have too much trouble [understanding] Hamlet!”

- Learn more about bisexual dating and how to connect now with bi, queer and open-minded folks.

Every single queer woman has grown up consuming heterosexual stories, whether they are about love and relationships or just part of the larger tapestry in a story about war or illness or moments in history. Somehow we’ve been able to find a part of ourselves in them, identify with a protagonist or learn something new. Are we just smarter or more adaptable than straight people? I’d love to say that’s the case, but I don’t think that’s the truth. What is true is that the powerful patriarchy that makes most of the decisions in what we watch, read or listen to en masse is still afraid that “gay” stories aren’t universal—that the only people who will watch a show with a lesbian lead are lesbians, unless she has a straight guy best friend or a male sperm donor she sleeps with. That is making it more palatable, somehow, which assumes that the straight consumer is either too homophobic and resistant or dumb enough that they cannot find any empathy or interest in someone who is different from them in at least one significant way. Never mind that they will watch science fiction and fantasy—the suspension of belief stops with sexuality.

I was so happy to hear Lisa Kron voice her opinion on this regarding her Tony-award winning show Fun Home, because most of the time, even the lesbians and gay men behind work that has LGBT themes can be a part of the issue. When One Big Happy was about to premiere, Ellen DeGeneres (an executive producer on the show) wanted to get the point across:

“It just happens to be a very funny show. It happens to have a lesbian character in it. It’s not like I formed a production company and said, ‘Bring me all your lesbian scripts.’ I’m not just going to be a lesbian machine that just turns out stuff.”

The idea that Ellen or anyone else would make shows about lesbians just because we want more lesbians is a bizarre notion that seems widely accepted. Yes, we want more visibility, but not at the expense of quality. If any media makers have taken a look at Twitter or Tumblr recently, they’d know we have a pretty high standard when it comes to the kinds of representation we have on television and film, and any non-fully fleshed out lesbian or bi character is going to give us pause.

It’s not just what we watch: It’s the music we listen to, too. Queer artists often refuse to discuss their sexuality out of fear it will ghettoize their music; that their openly discussing who they have relationships with has a bearing on who buys their albums and comes to their shows. And while this can be an issue for some artists, others are able to transcend labels, sort of like how Ellen has made her sexuality part of who she is but not a huge focus.

“There seems to be people finding incredible comfort and inspiration and empowerment in who we are. We’ve had people be like, ‘Oh, they’re gay’ or ‘Oh, that’s gay music’ or ‘I don’t like gay people,’ but we gain so much from being out that it kind of neutralizes that,” Tegan Quin told The Dallas Voice. “Like, I don’t care. There have been moments where it’s been dark, where someone is really homophobic, and I just wanna, like, run away and hide. Instead I just pick up a 2-by-4, metaphorically speaking, and bash through it and keep getting up on stage and being proud of who we are.”

Do queer women love Tegan and Sara? Hell yeah they do. And non-queer women and men love them, too. But even if the larger population of a show or concert is lesbian/bi-identified, how is that any less good?

If a story is told simply because it has a lesbian in it, it’s likely to not be very good. Just like if a story is being told about a straight white guy speaking Shakespeare—what makes us care? What makes us want to know more, to get involved, to feel invested in a stranger, a fictional character? Queer women have unique perspectives, and our way of moving through the world, experiencing it in different ways than what is generally force-fed to the public, is just as worthy of being shared—and, even more than that, necessary. Seeing us, hearing us, reading us humanizes us, which makes it that much more difficult for people to decide we are threats to them—a group that should be reviled, stopped or killed.

Can a Broadway show about a lesbian struggling with family issues, growing up different and finding herself help change the way someone thinks? Yes it can—and it can win Tonys doing so. Lisa Kron, Alison Bechdel and the other out women involved with Fun Home, as well as allies who believe in the power of storytelling, know how important it is that we stop pretending what we’re doing is any less watchable because we’re a part of it unless we insist otherwise.

Shows that have a premise of being “about lesbians” don’t last very long; shows that are about the human experience as told through the lens of a queer woman or several queer women will stand the test of time. Is Bound “about lesbians”? No, it’s about a woman who is involved in a mob scheme she desperately wants out of and finds an attraction to the hot female plumber next door. But is it not a lesbian story? Yes, it is—and one of the first mainstream films that succeeded with a female-female couple at the center, bringing in close to four million dollars to date.

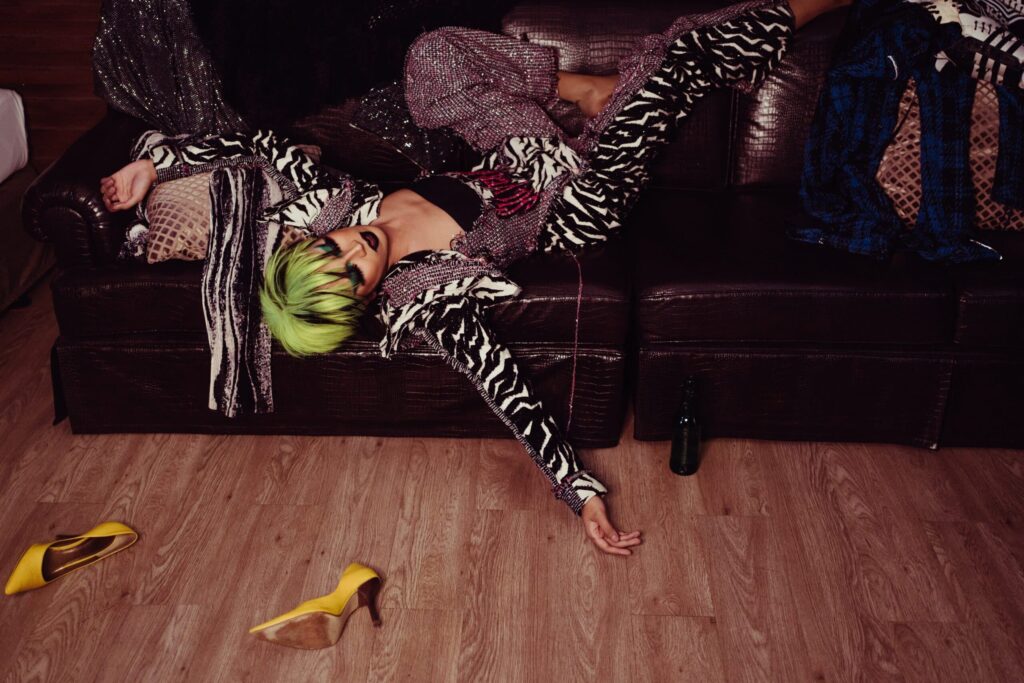

As for The L Word, it was both a show about queer women and telling lesbian stories from mostly lesbian women. But it had fully-realized characters and stories and also transcended a strictly lesbian audience. Many straight women, gay and straight men watched the show, just like we watch shows “about” them. Even if they watched it strictly out of voyeuristic curiosity, they had to take in a lot more emotional melodrama and lesbian lingo than actual girl-on-girl sex scenes. If it were truly the latter, The L Word would never have lasted six seasons on a premium cable network. (Sadly, the reality version was less nuanced, which is why it didn’t fare so well.)

The reality is that a lesbian audience is not big enough to make a show or artist a hit. (Unless maybe every single one of us tuned in, although that is unlikely because we have varying tastes and interests, just like other people!!!) But we are still a sizable group, and one that deserves recognition and representation like any others. (The fact that most of our most visible stories at this point are about white, able-bodied, cisgender and middle to high class lesbians is another problem itself!) It’s an unfair stigma and subsequent punishment to be given less opportunities based on the general population’s perceived one-track minds. If we all agree to move past that point, perhaps we can work to open them up, and we’ll all be better off for it.

Read the article on AfterEllen here.